Contents:

![]() Induction into the Army Air Corps

Induction into the Army Air Corps

![]() Grounded and wounded, but alive

Grounded and wounded, but alive

![]() The

German, the White Russian and me

The

German, the White Russian and me

![]() The Frankfurt

The Frankfurt

interrogation center

![]() Eat, drink, smoke, and be

Eat, drink, smoke, and be

creative

STALAG LUFT 1

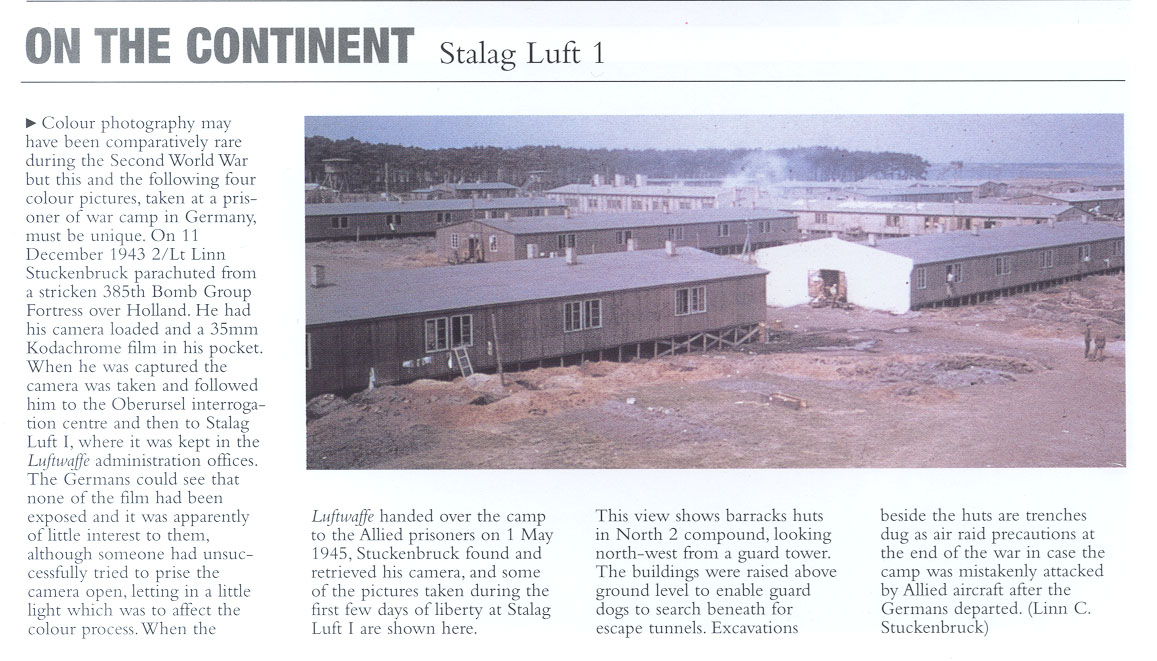

We re-boarded the train, but I don't recall anything until we got to the prison camp, Stalag Luft 1, Barth, Germany in Schleswig Holstein Province which is right on the Baltic Sea. We were marched from the train yards to the prison camp.

Barth Train Station

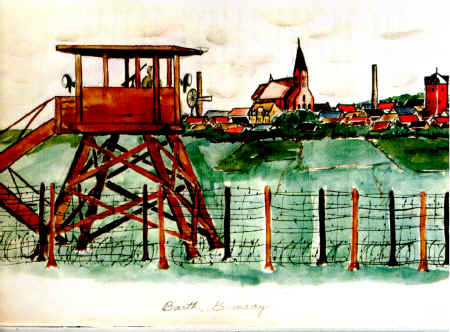

A watercolor of Stalag Luft 1, Barth, Germany, painted by prisoner Daniel E. McCarthy at the camp. Author's collection.

When we got to the prison gates, McGee was standing there. McGee said he had seen my name on the manifest of new prisoners coming in, and that is why he was there to meet me. He was surprised I was alive since he had been told that there were no survivors.

I asked him why he was there and he said because of "navigator trouble." When I was shot down, he was given an English navigator as a replacement. In a March raid, his plane was damaged. So he asked the navigator to plot a course to France. He wanted to ditch there rather than in Germany. The navigator mistakenly plotted a course over the Rhur Valley where the Germans had a heavy concentration of anti-aircraft guns. That is how he got shot down. There were two camps at this location (Stalag Lufts One and Two), and I never got to talk to him again.

I was placed in the prison camp hospital until I had enough strength to live in the camp compound. I remained under the hospital's authority.

Some strength returned to my right leg. There was damage to the femoral nerve that was crushed, which resulted in the complete loss of the femoral muscle. I still was not walking well.

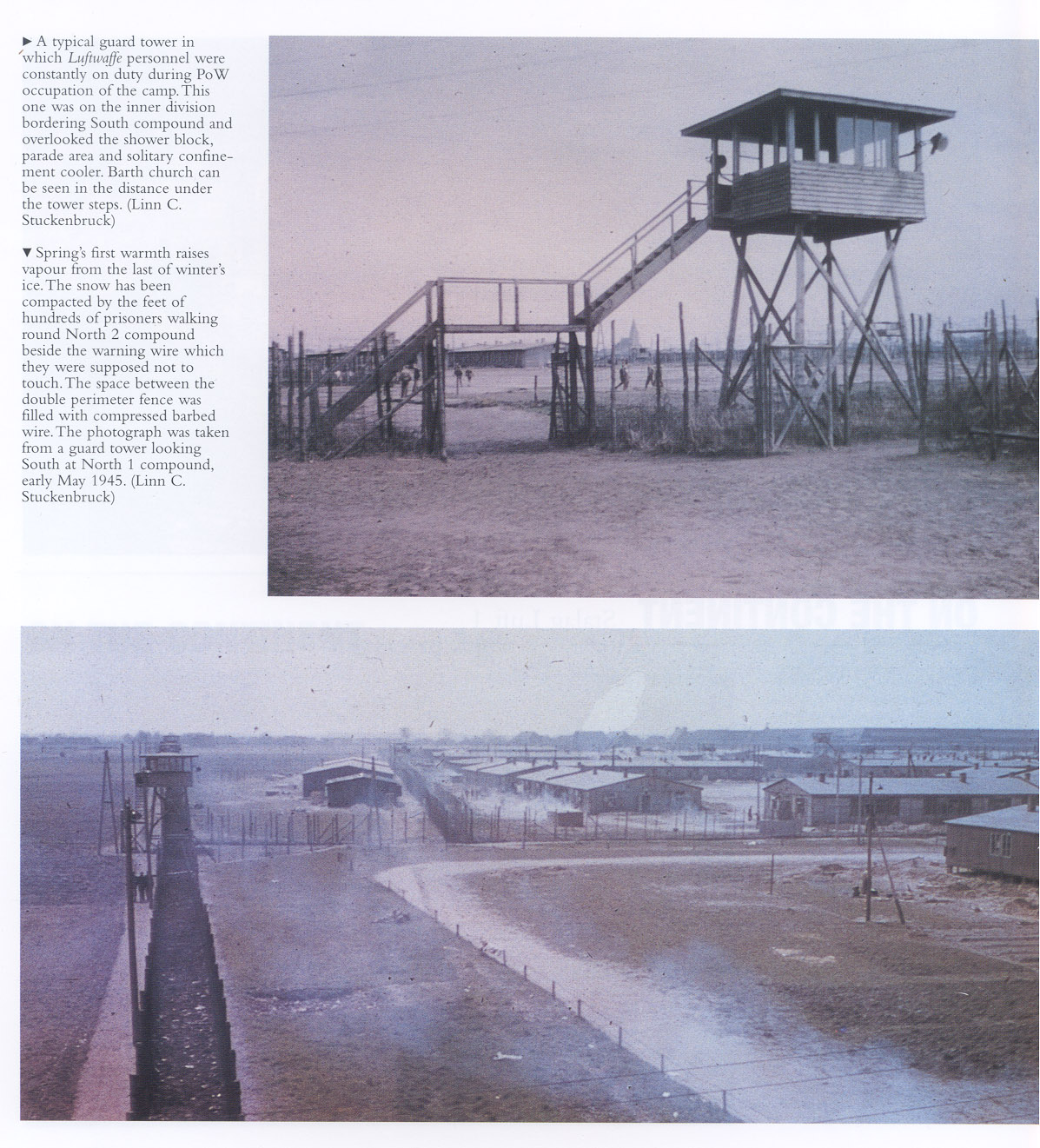

The camp consisted of about 25 buildings. There was a guard wire that ran around the perimeter of the camp and two barrier fences. The barrier fences, capped with rolls of barbed wire, were approximately 12 feet tall. The two barrier fences were separated by a distance of 8 to10 feet, and filled with rolls of barbed wire.

Stalag Luft 1 Color Pictures

Click to pictures larger images

There were guard towers at each corner of the compound and midway along each side. If you approached the guard wire, you were told to halt. If you crossed the wire, the guards would fire on you. The camp was designed in such a way that it was difficult to find an area concealed from view of, at least, one of the guard towers.

The barracks formed another perimeter inside the fencing and guard wire. There was a space between the back of the barracks and the guard wire that allowed a prisoner to walk around the barrack complex. The interior of the barrack's perimeter formed a large quadrangle where we had our roll call formations.

Roll Call Formation

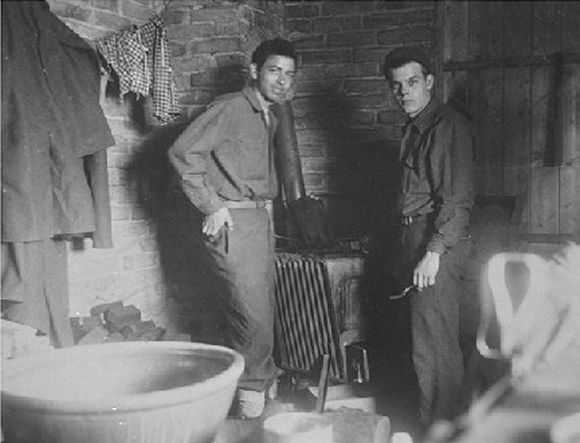

Each building had 12 rooms separated by a single hall with six rooms on each side. There were 14 men to a room in double decked bunks, along with one table, and a stove. We were allowed one lump of coal per man per day. There was one small eight inch by fourteen inch window at the top of the exterior wall, which was left open at all times for ventilation purposes. There were two other windows in the outside wall with heavy, wooden shutters that were locked one hour before sunset and unlocked one hour after sunrise.

Double-Decked Bunks

Heating and Cooking Stove

As P.O.W.s, We only had two duties. One was to stand roll call in the morning around 1000 hours. The guard counted us to see that no one had escaped or died during the night. The second duty was roll call again approximately one and one-half hours before sunset after which we were locked in the barracks. Not in the rooms, but in the barracks.

This permitted us to use the sanitation facility. It consisted of one room at the end of the barracks with porcelain bowls but no toilet seats. To defecate, you had to "find the boards" which were two planks removed from cartons that were about four inches wide by three-fourths inch thick and one-and -one half feet long. You placed them across the stool to keep from sitting on the porcelain.

The toilets were also used to flush the dirt from digging tunnels. It didn't take long to put most of them out of order.

We had a tunnel committee. If a prisoner or group of prisoners wanted to escape by tunnel, he or they had to present complete, detailed plans about where the tunnel would start, its progress, and the surface involved to the committee. The committee, then, would decide whether to give permission to go ahead with the tunnel. This was necessary because we might have eight tunnels leading from one barracks if there was no one authority to prevent chaos.

A tunnel had to be a minimum of 40 to 60 yards long, and, at least, seven feet deep. You had to exit it after dark.

One of the guys invented a bellows that would pump air to a tunnel shaft while you were working in it because the ventilation was so poor. There was no shoring, so a tunnel was only big enough for a single man to crawl through.

Disposing of the dirt was one of the main problems. The best method was to place a handful of dirt in your pocket and dribble it out as you walked the compound. Other prisoners would follow to mix it in by kicking and scattering it.

I could walk dragging one leg, but the paralysis eliminated me from the tunnel escapades. I knew very little about it, because the information was confined to the people in a single room working on a single tunnel--the fewer people who knew about it, the better. No tunnel provided a means for escape while I was there. However, a tunnel did provide the promise of escape, and kept people from losing hope.

One day, the Germans came into the barracks and ordered everybody out. They knew there was a tunnel that had been dug from that barracks, but they didn't know where the dirt had gone.

One of the German guards thought it might have been stored in the ceiling. He got up there with his flashlight, and confirmed it by yelling, "Ya, Commandant!" Then, he started to walk across the ceiling, but it collapsed under his additional weight. We were charged for the damage, which came out of the money that was paid to the Germans on our behalf.

In the POW camps, we were paid as though we were German officers. This money was placed in a fund against which the Germans charged us for everything we consumed such as razor blades, toothpaste, soap, and ceilings.

We were in double bunks, one above the other. There were no springs, just wood for slats. Each mattress consisted of a large sack, six feet long by two feet wide and probably six inches deep. The sack was filled with excelsior (fine, thin wood shavings). In the process of sleeping on it, the excelsior would crumble into sawdust. So, it was changed once a month. They would bring in a truck-load of excelsior, and dump it in the center of the compound. We would dump out our old stuffing and refill our mattresses with new.

We were issued one thin, gray blanket so we slept in our clothes because it was cold in the barracks. There was one ceiling lamp (electrical) which was turned out at about 22:00 (10 p.m.) each night.